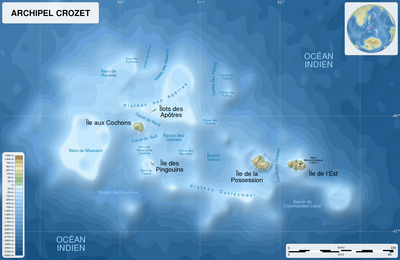

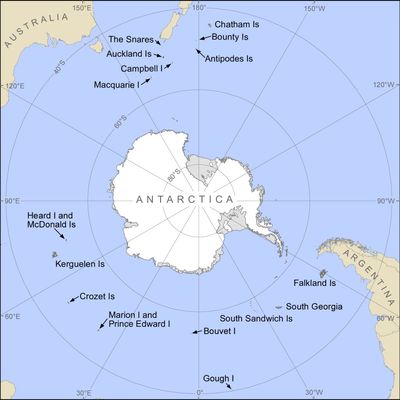

Pair of king penguins, Heard Island. Pair of king penguins, Heard Island. While I am not as well traveled as many, I have been very fortunate in the past to visit some of the most wonderful places nature has to offer, including places rarely visited by humans. These places are truly special, wild and isolated, raw nature at its most amazing. The places I am talking about are a series of small, isolated islands in the Subantarctic. Subantarctica lies north of the Antarctic region, circling the Antarctic continent, roughly between 46-60 degrees S latitude. What makes this part of the world so special are the many islands in the southern Indian, Atlantic and Pacific Oceans, isolated islands, desolate and barren save a few grasses, lichens and moss, and the seasonal visitors, those species which come ashore on these islands to breed. These islands are rarely visited by humans. Those islands truly in the Subantarctic region include, among others, Bouvet Island, Heard and McDonald Islands, the South Georgia Group, South Sandwich Islands, Kerguelen Islands, and Crozet Islands. A few of the islands support permanent scientific/weather stations, but most are deserted, except for the amazing wildlife which visit every year during the breeding season. While I was fortunate enough to visit South Georgia, Heard Island, and Kerguelen Island, it was my visit to the Crozet Islands which was the most special. And unfortunately, this post is all about what has happened to one of the most amazing spectacle of nature I have ever experienced. First, a bit of history. While I was an undergraduate student at Colgate University (NY, USA), majoring in biology, I was offered an amazing opportunity; a trip of a lifetime to New Zealand, Singapore, and south into the Subantarctic. The trip was made possible due to the generosity of Richard C. Damon (Colgate '50). I hope to write more about this amazing experience in later posts, but for now, this story is about the Crozet Islands. The Crozet Archipelago is located in the southern Indian Ocean, and is part of Terres Australes et Antarctiques Francaises (French Southern and Antarctic Territories). The archipelago includes five larger islands, and fifteen tiny islands. I was fortunate to visit three of the five larger islands, including Ile de l'Est (East Island), Ile de la Possession (Possession Island), and, Ile aux Cochons (Island of Pigs). This post is about our visit to Ile aux Cochons. We, including Richard, another student from Colgate (Stan S.), and a professor (Dr. Novak), along with almost sixty other passengers, were on a small ship, the Lindblad Explorer, operated by Lindblad Travel at the time. The 72.9 m long passenger ship, an ice-class vessel, was build in Finland in 1969, and was the first custom-built vessel for the expeditionary cruise market, and we were definitely on an expedition. We visited a number of islands during our travels, but our stop at Ile aux Cochons was incredible. We left the ship and boarded Zodiac boats for the ride to shore. Our primary destination on the island was a large colony of king penguins (Aptenodytes patagonicus), a bit of a hike from the beach where we landed. King penguins are the second largest species of penguins (emperor penguins are the largest), typically between 78.7 to 89 cm tall, and weighing from 12 to 16 kg. As we headed for the colony, we were first exposed to the smell, it was not pleasant, as the size of the colony turned out to be immense, and these large birds, year after year, deposited a lot of guano. Next, even before we could see the colony, we could hear it, and as we approached, it was almost deafening. And then, as we crested a small ridge, spread out before us was a massive colony of king penguins, estimated to be 1 million birds strong. This was, and still is, the most amazing spectacle of nature I have ever experienced. The smells, the sounds, overwhelming, and almost as far as you could see, in almost every direction, were king penguins. It was amazing. But since we visited in late 1980, things have changed, and unfortunately, not for the better. In 2018, Weimerskirch and others published a paper documenting a massive decline in the colony of king penguins on Ile aux Cochons. At the time we visited in late 1980, this colony was believed to be the largest king penguin colony in the world, and second largest colony of any penguin species. Weimerskirch et al. (2018) pointed out that the colony we visited was estimated to have about 502,400 breeding pairs (or a little over 1 million birds) in 1982, but recent estimates (December 2016) from satellite imagery and photographs taken from helicopters suggested the colony had shrunk to 50,926 pairs, a decline of almost 90%. The incredible colony we visited, that we experienced in late 1980, was decimated, and at this point, the exact reasons for the decline are unknown. While the exact reasons for the significant decline of birds in this colony on Ile aux Cochons is unknown, Weimerskirch et al. (2018) suggest a number of possibilities, including large-scale climatic events (e.g., Sub-Tropical Indian Dipole and El Nino Southern Oscillation) which have been shown to impact "foraging capacities", partial relocation of the colony, feral introduced cats and house mice, or disease or parasite outbreaks. The authors offered little support for any of these hypotheses (Weimerskirch et al. 2018). And surprisingly, the authors do not mention changes in food resources and/or climate change as a potential cause of the significant decline, even though these have been implicated in changes observed in other penguin species in the Antarctic (i.e., Barbraud and Weimerskirch 2001, Forcada et al. 2006, Trivelpiece et al. 2011, Klein et al. 2018). The southern oceans are among the fastest warming areas on the planet; mean winter air temperatures along the West Antarctic Peninsula and adjacent Scotia Sea have been observed to have increased from 5-6 degrees C (as reported in Trivelpiece et al. 2011). This, and subsequent loss of sea ice and changes in krill biomass, have been suggested as the primary drivers of significant declines in populations of other penguin species, Adelie and chinstrap penguins, over the last 30 years (Trivelpiece et al. 2011). Klein et al. (2018) modeled the impacts of rising sea surface temperatures (SST) on krill and their predators and model output suggested that rising SST could result in a decline of krill in the northern Scotia Sea of over 40%, with a concomitant decline in penguins of up to 30%. Others have also suggested that warming of SST could decrease krill biomass and drive reductions in the sizes of penguin populations (Barbraud and Weimerskirch 2001, Forcada et al. 2006). Krill (Euphausia superba) are a crucial component of food webs in southern oceans and areas around the Antarctic continent, but, king penguins are much less dependent on this food resource when compared to other penguin species such as chinstrap and Adelie penguins. Instead of relying on krill, king penguins dive deeper in search of fish (e.g., lantern fish) and squid. What is not known is how might warming impact food resources of king penguins. But, it would be hard to imagine that the significant warming of SST in southern oceans has not had an impact on king penguins, even though Weimerskirch et al. (2018) do not implicate climate change and subsequent warming of SST in the massive decline of the colony on Ile aux Cochons. We need more data, and we should be alarmed. What if other king penguin colonies, such as those on South Georgia, start to experience declines on the order of magnitude experienced by the population on Ile aux Cochons? We could have yet another species seriously threatened with extinction as a result of climate change. How long can we continue to let this happen? I was very fortunate to experience one of the wonders of nature, and now, that amazing sight is no more. References Barbraud and Weimerskirch. 2001. Emperor penguins and climate change. Nature 411:183-186. Forcada et al. 2006. Contrasting population changes in sympatric penguin species in association with climate change. Global Change Biology 12:411-423. Klein et al. 2018. Impacts of rising sea temperature on krill increase risks for predators in the Scotia Sea. PLoS ONE 13(1):e0191011. Trivelpiece et al. 2011. Variability in krill biomass links harvesting and climate warming to penguin population changes in Antarctica. PNAS 108(18):7625-7628. Weimerskirch et al. 2018. Massive decline of the world's largest king penguin colony at Ile aux Cochons, Crozet. Antarctic Science 30(4):236-242.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Brian C.L. Shelley, Ph.D.Scholar and scientist, conservationist, traveler and adventurer, photographer and writer, and lover of the outdoors, of nature, of Outdoor Adventure. After many years as a college professor, I was ready for a break. So I am taking some time off, to explore, and adventure more outdoors. I hope the content provided here will excite, entertain and educate. Enjoy the outdoors, Mother Nature has so much to offer. Archives

August 2024

Categories |

||||||

RSS Feed

RSS Feed